March 1, 2024

Recreating Captain Charles J. Biddle’s SPAD XIII Biplane

On a clear, late summer day last September, hundreds of visitors flocked to a small airfield in rural Pennsylvania for a long awaited and very special unveiling. For more than a decade, the staff and volunteers of the Golden Age Air Museum in Bethel had been building a functional 1918 SPAD XIII biplane. Not just any SPAD, this was a faithful replica—down to every last painstaking detail—of the plane flown by celebrated World War I ace Captain Charles J. Biddle.

Charles J. Biddle’s WWI SPAD XIII; Captain Biddle in his US Air Service uniform, 1918.

Golden Age Air Museum president Paul Dougherty had the idea for the SPAD in 2012. As an iconic fighter employed by the United States Air Service, it was a natural choice to add to the museum’s flying collection. Captain Biddle’s airplane was selected by Dougherty primarily because of its interesting heraldry, or paint scheme, but in large part because of its Pennsylvania connection, keeping in context the museum’s goal of relating the flying collection to Keystone State history. Experts in construction, the museum staff began the build using original French blueprints. It would be left to museum director, artist, and World War I aviation historian Michael O’Neal to ensure the accuracy of the final paint and markings.

Captain Biddle’s SPAD pursuing a German Rumpler, by Michael O’Neal.

Typically, a complete build from scratch by the museum staff takes three or four years. The complexity of the SPAD would triple that time and present a host of challenges in every phase of construction. Museum director of maintenance Michael Damiani, director Gerry Wild, pilots Neil Baughman and Rob Waring, museum member craftsmen, and a cadre of volunteers who contributed weekend time under the leadership of Dougherty, together fabricated and assembled every component of the airplane.

The SPAD replica during construction.

Several structural changes were made for practical and safety purposes. The wooden fuselage core was replaced with a steel tube frame, a modern aviation motor was employed to ensure positive ground handling, a steerable tailskid was added. But the remainder of the airplane is built the same as the original: fabric covered wooden wings and tail, no brakes, and period flight instruments. Attention to external details—subtle changes in the engine cowlings, period correct latches, stenciling, and placards, even fabricated dummy machine guns—all add to the authentic look.

Cockpit of the SPAD replica.

To complete the effect, the museum was able to precisely replicate the five-color French camouflage scheme used on the SPAD. Research from the late 1960s, based on the analysis of original fabric samples, provided the basis for this phase of the build. Using Sennelier pigments—a supplier of pigments to the French Air Service during the war—and aircraft dope, it fell to O’Neal to hand-mix the precise formulations. Pigment, aircraft dope, and the “secret ingredient” employed only by the French, reflective aluminum flake, were mixed to produce the striking and historically accurate, camouflage scheme.

The SPAD replica during painting.

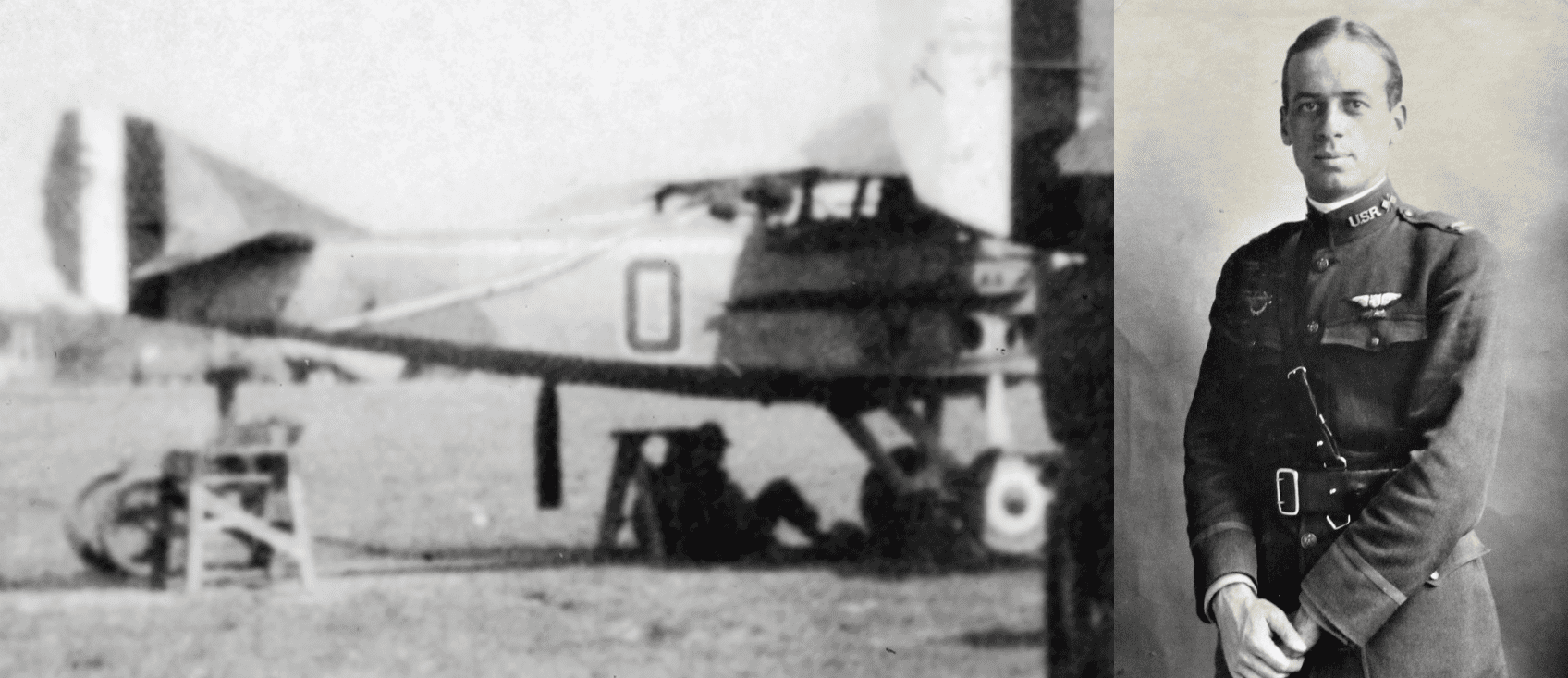

Yet on the morning of the SPAD’s unveiling, one element of the historic paint scheme was still missing: the grim reaper that identified all 13th Aero Squadron planes. The emblem is unique, departing from popular depictions of the reaper in several details. Instead of wearing a hooded cloak and carrying a scythe over his shoulder, this reaper, nicknamed Oscar, is a bare skeleton. He slings his blade low beneath his feet, as if slicing through the sky. Notches in the tool would have signified combat victories. Though created during World War I, versions of the emblem have remained with the 13th Squadron of the United States Air Force ever since.

13th Aero Squadron grim reaper Oscar emblem from the plane of Lieutenant William Howard Stovall.

As with all aspects of the SPAD project, Oscar’s omission was no accident, but part of a carefully orchestrated plan. Years earlier, O’Neal, with help from Don Henderson, editor of Invader magazine, the official publication of the 13th Bomb Squadron Association, had located the original brass template used to apply Oscar during World War I. This unusual artifact had been saved by Dr. Doug Kane, grandson of Lieutenant Earl F. Richards, the emblem’s original designer.

Paul Dougherty, Michael O’Neal, and Doug Kane positioning the Oscar template.

After a fascinating presentation, covering the history of the SPAD, the 13th Aero Squadron, and Captain Biddle, the replica plane was wheeled off the sunny field and into the shade of a hangar to receive its finishing touch. O’Neal positioned the brass template on the side of the fuselage—just behind the 0, overlapping slightly with the diagonal red, white, and blue banding—and traced its outline onto the canvas. Beginning with Dr. Kane, descendants of the 13th Aero Squadron pilots then took turns painting in Oscar’s ghastly visage. Captain Biddle was represented by grandchildren Charlie, Wing, Letitia, and Pamela and great-grandchildren Charley and Kate Biddle, Adam Blitzer, and Macklin Fishman. These descendants were joined by a larger contingent of spouses and Andalusia staff.

Michael O’Neal tracing the Oscar template.

The Oscar emblem was not complete when the ceremony concluded, but would be finished later by O’Neal. Visitors left the hangar to grab lunch, browse the tables of World War I and Air Force memorabilia, or even take a ride in an authentic 1929 WACO GXE biplane. The SPAD itself was not yet ready for flight, as the final part, and one not made by the museum, its propeller, had not been delivered. As much art as science, the laminated wooden propeller is currently being fabricated. Once delivered and installed, museum staff will begin flight testing, and, with luck, the summer of 2024 will see the SPAD flying over the farms and field of rural Bethel, Pennsylvania.

Charlie Biddle painting the Oscar emblem.

Pamela Biddle painting the Oscar emblem.

Charley Biddle painting the Oscar emblem.

The unveiling of Captain Biddle’s SPAD was a reminder that the historic legacy of the Biddle family extends well beyond Andalusia. While visitors to Andalusia can discover an exhibition gallery dedicated to his military service and time spent along the Delaware River, a trip to the Golden Age Air Museum offers a whole new perspective on his life — especially for those daring enough to take to the skies in a historic biplane!

The SPAD replica at the Golden Age Air Museum.

Written by: John Vick with Michael O’Neal

Photos: Andalusia Archives, Michael O’Neal, Richard J. M. Souza, and John Vick

© The Andalusia Foundation, 2024